|

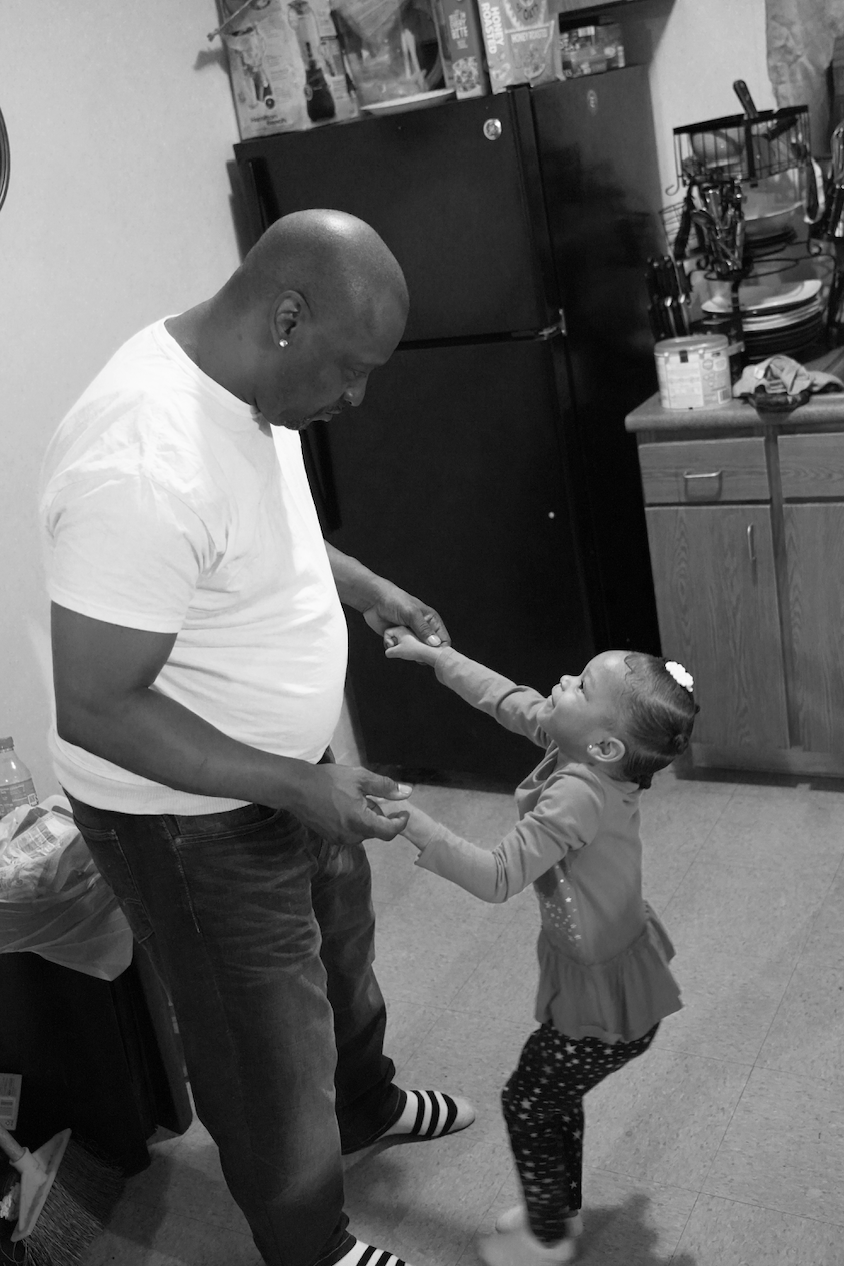

By Luke Elder Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman Though the Cabrini Green housing projects were torn down in 2011, "the row", a sequence of residences, still remains. Due to its close proximity to Chicago's downtown, Cabrini has been thoroughly gentrified, creating a mixed-income area with million-dollar flats just steps from low-income housing. "It used to be right there," Greg Fleming, who was raised in Cabrini Green, said. "Right where that big Target is. We used to hit baseballs at my building from there. Lot of white people. You never used to see white people." Cabrini was once a place of economic opportunity, but following World War II, nearby factories were closed, stripping the community of its economic base. Soon afterwards, the area began withdrawing services like police patrols and public transit stops. Photo Courtesy of Universal Pictures Cabrini Green has been the birthplace of many celebrities, yet it may be most famous for its depictions in Candyman, both the 1992 original and 2021 remake, with the former displaying the then-standing high-rises, and the latter displaying the Rowhouses. Cabrini, a place Mel Magazine's Eddie Kim calls "a vibrant community that, in real-life America, became the boogeyman representation of public-housing projects and the people who live in them," is examined in the 2021 film through the lens of gentrification. A commentary rooted in the real experiences of Cabrini's old residents, as expensive groceries and shops have overtaken their neighborhood. Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman The photo above shows Kenneth Hammond, a resident of Cabrini's Rowhouses, dancing with his granddaughter. Hammond worked with the Chicago Park District for nearly twenty years, trying to create places of safety for the young kids of the neighborhood. "I'm 53, born and raised over here." Hammond said. "I actually got a chance to tear down all the high rises with Hinnigan wrecking company." The violence and gang activity adjacent with Cabrini's reputation is exactly what Hammond hoped to eliminate--or, at least, mitigate. "We used to run "stop the violence" basketball tournaments," Hammond said. "Some of the best in the city used to come and show out." Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman "If a kid was in the park program," Hammond said, "when it came to ethics in there, how I worked with the kids, was to put myself in their shoes, because the kids I worked with lived in the same community I did. Some people would say, "oh, you think you're so much better because you're working with the park," but how can I be better than anyone when I live right below you? " Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman

Greg Fleming, pictured above, was able to bring himself out of Cabrini Green through basketball. Though he still maintains close ties with the Cabrini Green community, he is Roberto Clemente's head varsity basketball coach, on the other side of town. Fleming cited his experiences as his motivation to leave the community. "Just seeing my mother’s struggle. You know, by that time I knew I didn't want to be dead or in jail." Fleming said. "I really love sports. I really wanted to, you know, take that to the next level. It kept me out of trouble."

0 Comments

By Luke Elder

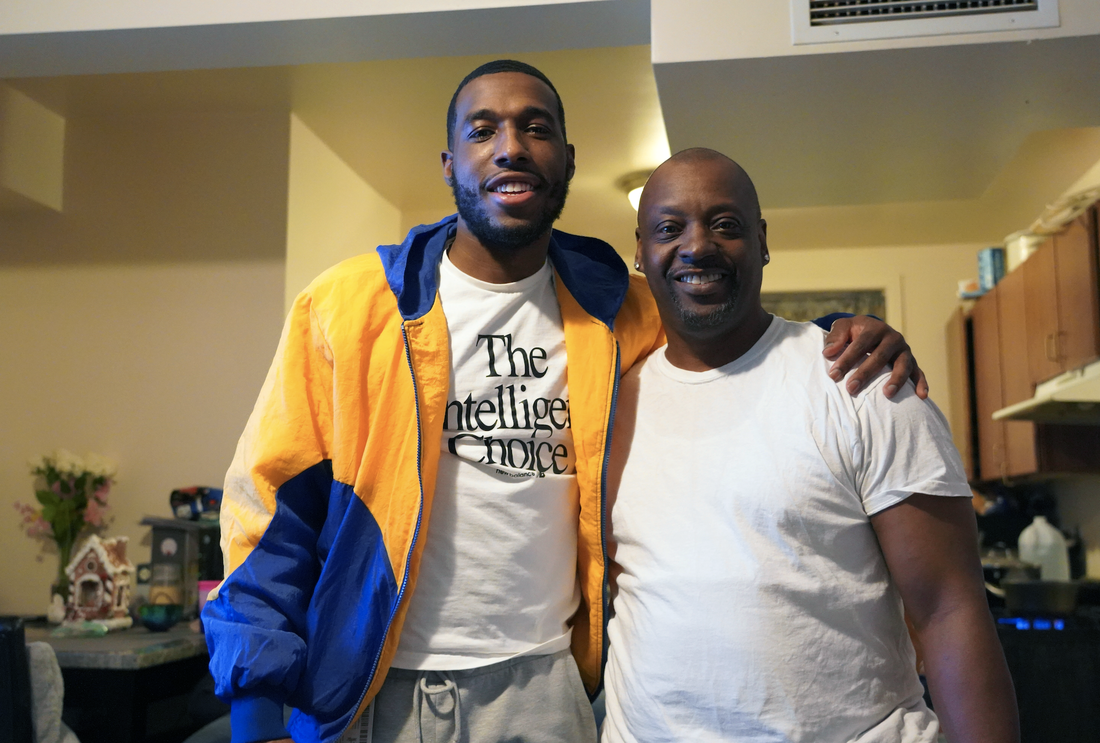

As a 6-foot-7 center at Roberto Clemente high, Lawrence Rowell is hard to miss. He towers over his classmates and teachers, and does the same for most of his competition on the court. With his high school basketball career coming to a close, Rowell is faced with the burden of a heavy question: what now? Presented with scholarship opportunities from Kennedy King and Wright College, it looks like that future will involve more basketball. “I can’t wait to play at a high level,” Rowell said. “I never thought I was going to be able to.” Though basketball can pave the way for academic opportunities, Rowell’s heart is torn between two passions: basketball and culinary arts. To ‘cook’ someone is a slang term for beating an opponent in basketball, so Rowell hopes that college will bring cooking in two ways. “I’m not sure which is more important to me yet,” Rowell said. “I’m going to keep cooking while I’m in college. Kennedy has culinary, but everything is paid for at Wright.” Blessed with two unique talents, the doubters have always come for Rowell. Not becoming a starter until his senior season, he was told by teammates and coaches that his height is undeserved; that he’s tall for no reason. “They said they could do better with my height, or tell me I’m no good.” Rowell said. “I’m just here to prove a lot of them wrong.” Despite proving his worth on the basketball court, his dreams don’t necessarily involve points or rebounds. Rowell began to cook at just four years old, after watching his family make breakfast in the kitchen. “Every Sunday morning, my father would make me pancakes, grits, and a ton of sausage and eggs,” Rowell said. “Every time, the smell of the food would make me so happy. My dad and my auntie inspired me to cook.” At just ten, Roval began to consider culinary arts as a career. “I started to make big meals for my family,” Rowell said. “It would be so quiet at the table, all you could hear was forks and spoons hitting the plates. Everyone would tell me how good the food was.” When Rowell isn’t on the basketball court, you can find him manning the grill at family cookouts or making meals for friends. He’s skilled at cooking many different styles of dishes, but he wasn’t willing to share any of them. “I like to cook seafood, breakfast and soul food.” Rowell said. “A detailed recipe? A lot of them are secret recipes for generations.” Rowell speaks about the intricacies of cooking like an academic does a research paper, or a conductor does a symphony. It’s almost like his persona switches as he begins to speak. “I always loved the idea of how some flavors mix so well together,” Rowell said. “How one small detail can change how a dish tastes.” There was a time when neither basketball nor culinary arts were in the cards for Rowell, after struggling early on academically. He never liked to study, but found academic success in high school. “My grades weren’t always this good,” Rowell said. “I hated school–I would do the work, and not turn it in just because it was so boring. That changed in sixth grade when my auntie had a talk with me. She really changed me. Since then, good grades. I just want to make my family proud.” By Luke Elder Greg Fleming standing outside the "Row", the only remaining buildings of the Cabrini Green projects. Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman Greg Fleming, Roberto Clemente’s boys basketball coach, leads with intensity. Making mistakes results in an earful full of rhetorical questions and curse words. From the outside looking in, he’s just another young coach with a chip on his shoulder, but Greg Fleming’s bearing the weight of his community. The famous Cabrini Green community, known as well for Candyman as it is for gang violence. A place imagined cinematically for the American public. “I’ve met a lot of people who look at Cabrini as if it’s a bad place,” Fleming said. “Me on the other hand, on the inside, growing up here, it made me who I am. It’s a project, so we get looked at ten times worse than the average place. The older guys were always in my ear, constantly, you know, reminding me keep going, keep going. They’d threaten me, saying ‘if I catch you on drugs I’ll kick your ass.’ I really think that helped me. So many people pushed me, and I could thank so many people. What I do, I do for my community. I try to represent my community in the best way that I can, try to show people outside Cabrini that there are good people from here.” Amongst the crowd of supporters is Fleming’s cousin, Kenneth Hammond. Wearing a toothy grin and diamond earrings while he cooks sloppy Joes for his family, Hammond remembers Greg’s time in Cabrini as a boy, as well as his own. “Lil’ Greg is one of the special ones in the family, we don’t have a lot of successful athletes,” Hammond said. “So he was the oldest kid in his family, and he became a real, responsible mentor young– taking care of his younger siblings in the household. So that right there, put Greg at a whole different standpoint from a lot of us coming up, you know, I was raised in a house with six other siblings with just my mom.” Hammond sees a great deal of himself in Fleming, sharing far more than just similar family upbringing. Violence is something Hammond and Fleming saw plenty of growing up. It’s an unfortunate–and inevitable–aspect of their community. “Greg and his little brother were really close, like ‘yin’ and ‘yang’, and his brother was also a guy who had a chance to lead the community, and make something of himself.” Hammond said. “Unfortunately he was lost to gun violence. My oldest son was recently lost to gun violence, too. The temptation is so strong once you leave your house out here, and I know, because my brother was a notorious gang leader.” Though Fleming was surrounded by shootings and gang activity, he worked hard to avoid what felt like the only path for young men in his community. Though later success was found in basketball, baseball was Fleming’s first love. Fleming would later be introduced to Roberto Clemente Community Academy as a baseball prospect. “During the summer when I was a kid, we’d have baseball games in the morning.” Fleming said. “We’d come back to Cabrini, with our uniform still on, and play ‘til it got dark.” Greg was in fourth grade. At the time, his cousin was working with the Chicago Park District, who ran a program to help keep young students off the streets. Some kids came to get a meal if they couldn’t get one at home, but most came as a place of shelter–of solace. Fleming alongside his cousin, Kenneth Hammond. Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman “When lil’ Greg was coming up, and someone wanted to be rough or not follow the rules of the park, we’d say, “we’ll give you two, three days up out of here and see how you want to act.” Hammond said. “Because we all knew, at a certain time of the day, no matter if you were an athlete or just hanging out, you wanted to be in the park. We’ve been surrounded by this all of our lives, so you need to have a strong mentality to want something more in life than just this. To want something for the future.” Athletics was a helpful incentive to keep Fleming away from the violence-laden streets, but he attributes his avoidance with Cabrini’s drug trade to his mentor, Deepak Devaraj. In 2004, Devaraj was struggling to find fulfillment beyond his workplace in trading. Blindly, Devaraj was exploring Catholic charity programs and stumbled upon one called “Cabrini Connections”. Knowing nothing about it, he searched online and found that it was a mentorship program, on Wednesday nights. “We were sitting in a classroom, and there's probably 15 or 20 of us up front, that were kind of adult-ish. There's probably, you know, 25 or 30 kids in the room,” Devaraj said. “So the administrator of Cabrini Connections gave a speech, and as soon as he's done, Greg looked straight at me. He points to me and he goes, “I want you to be my mentor.”” It was through seeing Greg’s background and beginning to understand his struggles that Devaraj found purpose in their partnership, and the two quickly formed a tight bond that would last a lifetime. Devaraj said the two were a perfect pair, because Fleming was in need of love, and he had love to give. “I realized, like, this can go beyond just learning how to read and solve math problems. So while it started in the classroom, it kind of morphed into him actually just becoming part of my family. And I always say it's like he's the oldest child I never had and he's the younger brother I never had.” Devaraj was quick to note Fleming’s confidence and outgoing nature from an early age, but was sure to imbue a sense of hard work while showing Fleming other options in life; other cultures and neighborhoods. “He always tells me, “dude, if it wasn't for you, opening my eyes to what really existed in the world.” Devaraj said. He's like, “there's no shot in hell I would ever be doing any of this. But once he saw what was on the other side, once he saw a functional family eating dinner together, a functional person getting up every morning at 4:30 to go to work, it showed him like, I'm not afraid to put in the work. So once he once all that clicked, it was kind of game on.” Devaraj remembers being thrown first hand into Cabrini Green’s projects, when a young Greg found it all to be too much. “I’ve had to go to the projects to go find him because sometimes he would kind of disappear a little bit. Then I would have to go up to his house–going up to the eighth floor of the [Cabrini] towers. It's not such a welcoming site, when you're an outsider. It was one of those things where he’s just a part of my family and, and he will always be.” Through a difficult upbringing, Fleming was molded into a mature young man and gifted athlete. So much so, that he was offered a basketball scholarship to attend Grand Rapids Community College. “They were a powerhouse at the time. I kept my head down in the classroom and had a good ass season. I ended up picking up like six offers after that,” Fleming said. “Afterwards, I ended up at Lourdes University, had one of the toughest coaches ever. Coach Smith. He was this big black dude, and when I had just met him, I had lost my brother. I didn’t even know if I wanted to take the scholarship, but signed the letter of intent, and then a month later my brother is murdered. I was excited to go to school, but at the same time I just lost my brother.” Fleming finished just short of a degree due to personal reasons, but was thankful for the chance to experience life outside of his hardened upbringing. “It was fun. Being able to play ball, go to school for free,” Fleming said. “Just opened my eyes to a different viewpoint. Made me a better person, being around all these positive people.” Devaraj was confident that Fleming could still find a way to finish the last few credits of his college degree. He wondered if Fleming might’ve finished if he were closer to his support system. “He'd always come to eat dinner and hang out. We were together all the time,” Devaraj said. “When he moved to college, then it was more of like we would talk on the phone, you know, once a month kind of thing, maybe a little bit more often if there was some trouble going on. But you know, it's just hard when you're not in the same city. Like, I went and watched his first game of the season, and we’d talk on the phone once a while, but it was much easier when he was in the city.” Finishing aside, the opportunity to have a basketball scholarship and “make it out” of Cabrini was exceptional, and Fleming’s community noticed. Now, as one of Chicago’s youngest head basketball coaches, Greg is presented with a task not too dissimilar to the one his cousin and mentor had managed all those years ago. “Greg is doing the same thing, now, but it might take a village to do that with the way things have changed,” Hammond said. “Greg is future representation for our family. A lot of things might happen, but he’ll be a successful man. Maybe he’ll buy me lunch. He don’t owe me nothing, but he knows I love to eat.” The love and care shown by Fleming’s supporters is an unquestionable product of the community, but also, the life experience Fleming has overcome to become a mature leader. “One of the reasons he's going to have a tremendous amount of success is, there's no high school or junior high kid that's going to be able to bullshit him, right?” Devaraj asked. “I mean, the guy has seen it all his brother was murdered. You know, he's seen the gangbanging and seen the drugs, he's seen everything firsthand. So it's like, you know, he knows what happens when you become a product of the system. And I think in a weird way, I think the players respect that and look up to him for that.”  Fleming with his mentor, Deepak Devaraj Photo Courtesy of Luke Elder/The Elder Sportsman As a first-year varsity coach given the job just before the season, Fleming was left with few opportunities to prepare and recruit players before the preseason’s start in the fall. Fleming is not a stranger to being left with few options, so a positive outlook was his natural inclination.

“It was definitely frustrating. I had to kick a few kids off the team for grades, not being coachable or undisciplined,” Fleming said. “I laid down the expectations that this is what it’s gonna be. We struggled, but it was a learning experience for me and my team, so I feel blessed for that. I learned a lot.” Fleming knew that giving back to his community, one way or another, was always the goal. “I think I wanted to help kids my whole life,” Fleming said. “I had a chance to play [basketball] overseas, but I turned it down. I came back home, and the Clemente coach at the time reached out to me and asked me if I wanted it, and I said yes. I wanted to help kids, kids like myself that were unfortunate, that didn’t have the best resources. Kids that had single moms, that don’t got a lot. I figured out quick that it was my purpose, my why. I think God brought me back to Chicago. I’m just trying to do a good job. I think I’m doing a good job.” “A great job”, Hammond added with a smile and a hand on Fleming’s shoulder. “Lil greg plays a big part in our community, our neighborhood. I know that I appreciate it, and that others appreciate him. It’s important to our community, because our future is our kids. Greg’s playing a big part of that, helping them come up. There aren't a lot of lil’ Gregs over here, still. He stayed connected to where he’s from.” If Greg’s coaching career were over tomorrow, he’d still have a community of people to back him. Proud of their roots, Cabrini Green’s residents wear their hardships like a badge of honor. “The temptations are really hard to fight, and the expectation is so high once you come up out of the inner city. Especially from Cabrini, famous Cabrini,” Hammond said, “We’ve had actors, singers, athletes come from here.” No stranger to the difficulties faced by those he now mentors, Greg Fleming is working to be enshrined amongst the Cabrini success stories. His tool? A basketball. It was his way out, and he hopes it’ll be a chance for others like him.

By Luke Elder

The 2022-2023 season is close to 9 months away, but the presence of AAU and off-season training makes high school basketball feel like a full time sport. Not a full week after Clemente’s disappointing loss to Holy Trinity in the first round of the Divisional, they are back in the gym for training and practices.

It’s never too early to look ahead, right? Here are three predictions for Clemente’s 2023 season: John Rivera will step up big

The young freshman began to prove his ability to lead throughout the season, slowly (but surely) assuming more on-court responsibility and playing with more efficiency. He could use a little interview practice, but his game is on the upswing. Clemente is in desperate need of a player-captain.

The lack of commitment shown by soon-to-be senior and leading scorer Jamarion Latzzis, who often misses practices and lifts, gives no reason for anyone to believe he’s suited to fill that role. Rivera, who played his first year of organized basketball this year, showed the maturity of a senior by the season’s end. “He’s learned to control his temper, his emotions. He’s learning how to deal with adversity,” head coach Greg Fleming said of Rivera. “He’s mature, I think he’s a guy who’s committed, and I think he’s going to set the tone for my program for the years to come. No doubt.” Rivera’s maturity is apparent, especially when compared to the frustrated, temperamental kid I met a few months ago. He was committing sloppy fouls, making freshman-type plays. Now, he leads his teammates in the weight room and is the first one in the gym for training. He talks a big game to his teammates, but has begun to back it up. “The whole team just needs a better work ethic,” Rivera said. “They’ve got to devote themselves to basketball.”

new recruits will help fill the gaps

Fleming and company have spoken about “the recruits coming in” like the messiahs of Clemente basketball. Those that’ll carry them to the promised land. Maybe they’re right. While I sat in for a Sunday afternoon practice (when the recruits can join), it was evident that these kids were hungrier, and in some cases, more talented than many of Clemente’s young varsity players.

Julio Malone holding a JR Hoops trophy

Photo courtesy of Greg Fleming

A key among the mix is Fleming’s younger brother, Julio Malone. Malone was recently selected for the “Rookies Game”, where some of Chicago’s top eighth graders face off. Fleming expects Malone to make a serious varsity impact “from day one.” I got the chance to watch Malone in action during that Sunday practice, and it was evident, even in his young age, that his quickness and shooting ability is well-curated. He’s a head above the rest.

Just below .500

Hear me out, I don’t have any delusions of grandeur. A team, even with some young guns to boast, does not go from 4-22 to a conference championship in a year’s time. It may take even longer, but five of Clemente’s losses were decided by just eight points or less. A little bit of sharpened defensive effort and a few more buckets make those different games. There's no reason to believe, based on that evidence, that some adjustments could make Clemente an 11-15 team.

Though the loss of dominating paint presence Lawrence Roval hurts Clemente’s ability to intimidate down low, a year of varsity experience under the belts of freshman guards Levarus Grayerr and Derrick Carter should easily make up the difference. In Clemente’s heavily undersized blue conference, the two six-foot-two guards will command the elbows defensively in Fleming’s two-three zone defense, eliminating the need for Roval’s size. They’re both young enough that there is room to grow. Clemente will miss the defensive prowess that came with Roval and fellow senior Jacob Perez, but the influx of talented, hungry recruits and older players buying in could make Clemente a dark horse in the blue conference. We’ll just have to wait and see.

By Luke Elder

Despite head coach Greg Fleming out sick, and many players absent, Clemente hoops was able to squeeze in an off season workout with assistant coach Brandon "Cheese" Onuselogu. "Cheese" is a licensed physical therapist and well versed in fitness training (evidenced by his biceps). He took the four young players that made it through a lower-body strengthening session, hoping to help them with fundamentals.

Though most Clemente players are inexperienced in the weight room, the ones that showed up are committed to the work. They're highly competitive when talking basketball, though competition is many months away. Freshman John Rivera and Sophomore Paul Moore banter. "You know you couldn't guard me one-on-one," Rivera said to Moore, "I'm too strong." "What's your points record in a game?" Asked Moore. "That's what I thought."

"I'm just trying to stay committed," sophomore Chris Escobar (above, right) said, "get better in my progress. Get bigger and stronger."

|

AuthorLuke is a Master's student at DePaul, and a fan of all things sports. Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed